da Leadership Medica n. 8 del 2005

ABSTRACT

Aging of the population is characterised by a marked increase in the number of subjects aged eighty years or more (the oldest old). In this group frailty is extremely common. Frailty is a recently identified condition, resulting from a severely impaired homeostatic reserve that puts the elderly at highest risk for adverse health outcomes, including dependency, institutionalisation and death, following even trivial events. Geriatric medicine proposes an original methodology for the management of frail elderly subjects, the so-called “comprehensive geriatric assessment” (CGA), and a model of long-term care, which have been shown to reduce the risk of hospitalisation and nursing home admission, with a parallel decrease in the expenses and an improvement of the patient’s quality of life. The effectiveness of the long-term care system depends on:

1) the availability of all the services that are necessary for the frail elderly, both in the hospital and in the community;

2) the presence of a coordinating team, the comprehensive geriatric assessment team, that develops and implements the individualised treatment plans, identifies the most appropriate setting for each patient and verifies the outcomes of the interventions;

3) the use of common comprehensive geriatric assessment instruments in all the settings;

4) the gerontological and geriatric education and training of all the health care and social professionals.

Fig.1 - An "extreme" case of a frail elderly person: "… patients who have been historically ignored by traditional medicine as numerically irrelevant and professionally unrewarding because incurable and "difficult" to handle through healthcare and social care facilities, also because they are often disturbing …" (Senin U., 1999).

Fig.1 - An "extreme" case of a frail elderly person: "… patients who have been historically ignored by traditional medicine as numerically irrelevant and professionally unrewarding because incurable and "difficult" to handle through healthcare and social care facilities, also because they are often disturbing …" (Senin U., 1999).

To the question as to "What is the typical geriatric patient?", the Editor of Textbook of Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, responds "Think of your oldest, sickest, most complicated and frail patient …. He or, more frequently, she often presnts with multiple disabilities covert as well as overt. Thus while signs and symptoms might suggest, for example, pneumonia as in the younger patient, limited physiologic reserves in multiple

systems may lead to complications vastly reducing the remaining life span of the patients…. Often also presents atypically…." (1999). (Fig. 1).

Analogously, Linda Fried, director of the Centre on Aging at John's Hopkins Universityin Baltimore (USA) states: "The identification, evaluation, and treatment of frail older adults is a cornerstone of the practice of geriatric medicine." (2001).

INTRODUCTION

The history of medicine is marked by the constant onset of new clinical entities, which are given a name that precedes research designed to build knowledge on their real nature. Typical recent examples are NASH (Non-Alcoholic Steato-Hepatitis) and AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome). Today, due to the quick population aging process, which has been taking place since the mid-20th century, the one who attracts the attention of healthcare service and facility workers is the frail elderly person, a clinical entity who has been identified and described by geriatric medicine in the past 15-20 years.

Frailty affects a significant percentage of the elderly population, especially the oldest old, with a considerable impact on our "welfare" system due to the great need to find solutions to meet the demand for social and healthcare, which patients who suffer from this condition require and will increasingly ask in the future.

On the basis of statements made by the most authoritative members in the world of geriatric medicine, the frail elderly person is a geriatric patient. It is in fact on this patient that geriatric medicine has built a heritage of scientific knowledge, processed a targeted assessment method - the so-called comprehensive geriatric assessment - and proposed and experimented with suitable healthcare models.

And lastly Morley, Director of the Department of Geriatrics, St. Louis University (USA), adds: "Geriatrics finds its greatest expression in the management of the frail because it is this individual who most escapes the attention of the specialist in internal medicine and other specialists". (2002)

On the other hand these patients have been historically ignored by traditional medicine because they were numerically irrelevant till recent times and especially because they were neither "scientifically" interesting nor professionally rewarding since they were in practice incurable, "disturbing" and difficult for social and healthcare facilities to manage.

Though there is no unanimous agreement on its definition, the expert clinician can recognise the frail elderly person. Hazzard writes (2004) "… a man, or more often a woman, who lives on a razor’s edge, balanced between maintaining his independence and the risk of a tragic cascade of pathological events, disablement and complications, which only too often prove to be irreversible, is one of the most complex problems physicians and all healthcare professional figures have to face… It is a great challenge as the coexistence of multiple chronic and progressive diseases is the rule, while simple problems, which are spontaneously solved or which are easily treated, are the exception… besides, these mutually interacting diseases appear in an atypical or non specific manner, thus "darkening" all attempts to formulate a precise diagnosis…… These are individuals, whose reduced functional reserve and limited recovery capacity increase the risk of weight loss, malnutrition, dehydration and adverse reactions to drugs and to medical and surgical interventions… The complex network of all these factors’ interactions is frequently the cause of the onset of one or more geriatric syndromes, which probably, more than any other element mark geriatrics as a medical specialisation: confusion, falls and fractures, urinary incontinence, depression and dementia, to mention only a few".

From an operational perspective the frail elderly person is generally old or very old and suffers from multiple chronic diseases. Clinically unstable and frequently disabled, he often presents social and economic problems, especially solitude and poverty. (Figure 2).

Fig.2 - Frail elderly: the domains of frailty.

Fig.2 - Frail elderly: the domains of frailty.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGICAL DIMENSION

The prevalence of frail patients in the elderly population varies depending on the criteria used. In a longitudinal study conducted in the United States on a sample of about 5,000 patients aged over 60 years living in their homes, (Cardiovascular Health Study 1989), 7% proved "frail" with an incidence of 7% at three years (excluding those suffering from Parkinson’s disease, mental deterioration and depression). These patients presented a significantly higher risk of mortality, falls, hospitalisation and disablement than the “non frail”. (Figure 3)

The same study revealed that the prevalence increased exponentially in older patients involving 3% of individuals aged between 65 and 70 years and 26% between 85 and 89 years with a greater incidence in women than in men (7% vercascata. sus 5%).

According to the American Medical Association about 40% of people aged over 80 are carriers of frailty, just as the great majority of 1.6 million elderly individuals hospitalised in nursing homes in the United States is frail.

Fig.3 - Risk of adverse events in the frail elderly compared to the non frail at the close of three years of longitudinal observation. (Fried LP. 2001).

Fig.3 - Risk of adverse events in the frail elderly compared to the non frail at the close of three years of longitudinal observation. (Fried LP. 2001).

PHYSIOPATHOLOGY OF FRAILTY

Frailty is the final result of a process of accelerated psychophysical decline, which tends to progress once triggered. Many experts agree on the fact that frailty is the expression of the body’s

extreme homeostatic precariousness due to the concurrent impairment of more than one anatomical and functional system when aging effects are associated with damage resulting from an inadequate lifestyle and diseases in progress or suffered during a lifetime. (Figure 4)

These are the reasons why the frail elderly person is a patient who is characterised by inability to react effectively to events which disturb his already precarious balance, such as for example unusually high environmental temperature, worsening of chronic diseases, the moderate onset of a serious disease, a physically and psychologically traumatic event, a diagnostic procedure that is either inconsistent or conducted without due caution and an inappropriate therapeutic intervention.

Naturally a greater degree of frailty involves a greater risk that even the most trivial factors will trigger a chain of events in the short term with a catastrophic outcome (the so-called "decom-risulterebpensation cascade"). (Figure 5).

Fig.4 - Intrinsic and extrinsic factors of frailty.

Fig.4 - Intrinsic and extrinsic factors of frailty.

Fig.5 - Decompensation cascade in the frail elderly. *LUT: urinary tract infections.

Fig.5 - Decompensation cascade in the frail elderly. *LUT: urinary tract infections.

CAUSES OF FRAILTY

Today a reduction in muscular mass (sarcopaenia) that significantly impairs physiological functions is considered a central triggering factor of frailty. (Figure 6)

It has in fact been proved that very evident sarcopaenia is associated with reduced muscular strength, power and resistance; reduced basal metabolism and increased adipose mass; accelerated loss of bone mass; postural instability; and lower thermoregulation capacity. These trends increase the risk of functional decline, falls, fractures, hypothermia, hyperthermia and cardiovascular disease.

Frailty also causes progressive dysregulation in some neuroendocrine systems with impairment especially of the following ones: hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis, whose altered functionality involves a chronic increase in blood cholesterol followed by a gradual resistance to insulin, reduced immune defences, hippocampal neurodegeneration, to which the increased muscle catabolism, cardiovascular risk and risk of infection must be traced, and mental deterioration;

the sympathetic system, whose increased basal activity contributes towards the increase in blood cholesterol;

anabolizing hormones – especially sexual ones, GH and DHEAS - whose reduction accelerates the loss of muscular and bone mass.

The immune system too could be involved since certain studies have documented a greater vulnerability towards infections and higher inflammation indexes expressed by an increase in cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-a in the frail elderly, compared to the non frail group. On the basis of this data a recently introduced theory stated that a chronic proinflammatory state is at the root of frailty and the accelerated muscular catabolism, increased stimulation of the adrenal-cortical axis and an increased synthesis of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), which is a powerful anorexigenic agent, can be partly traced to it.

Other biological mechanisms would however be involved in causing frailty since this condition is often also characterised by the presence of anaemia, low albumin, total protein and blood cholesterol levels and other signs of protein caloric malnutrition, higher levels of plasma osmolarity and high levels of D-dimer, which is an indicator of fibrinolysis and inappropriate activation of coagulation.

The latter condition has proved to be associated with a higher risk of functional decline and mortality in the elderly.

There is a basic conviction that the elderly reach this condition after a long course, which comprises progressive phases and results from the negative synergy of many factors - inflammatory, metabolic, endocrine, functional, psychological, etc. – which enhance the loss of homeostatic skills in various organs and systems due to aging, especially in the great integrating systems (immune and psychoneuroendocrine), thus leading individuals towards a condition of increasing vulnerability.

Fig.6 - Sarcopaenia and frailty: the pathogenetic processes involved. CV: cardiovascular - CNTF: ciliary neurotrophic factor; - INF: interferon

Fig.6 - Sarcopaenia and frailty: the pathogenetic processes involved. CV: cardiovascular - CNTF: ciliary neurotrophic factor; - INF: interferon

CLINICAL FRAILTY

An analysis of literature on frailty thus characterises the condition from a clinical perspective:

- high susceptibility to develop acute diseases, which are expressed by atypical clinical pictures (mental confusion, postural instability and falls);

- reduced motor skills and immobility due to serious asthenia and adynamia that are not entirely justified by the diseases present;

- rapid fluctuations in health even during the same day with a remarkable tendency to develop complications (decompensation cascade) (Figure 5);

- high risk of iatrogenic problems and adverse events;

- slow recovery capacity, which is almost always only partial;

- constant request for medical interventions;

- frequent and repeated hospitalisations and the need for continuative care; high risk of mortality.

Considering these patients’ high complexity, extreme instability and vulnerability, their management requires a solid gerontological culture, extensive clinical expertise combined with "common sense" and long standing experience, but the "motivational" aspect must play an essential role. These are patients, whose only possibility of obtaining a significant outcome is entrusted to the systematic application of the evaluation method, principles and interventions typical of geriatric medicine and the presence of an integrated specifically designed and organised hospital and territorial network of facilities and services.

THE ITALIAN HEALTHCARE FRAMEWORK

The current social and healthcare organisation is the expression of a society, which had many healthcare requirements mainly arising from acute infectious diseases that decimated infant and young adult populations. Chronic diseases, when present, were only a short-term issue and the disabled were basically registered disabled ex-servicemen and registered disabled civilians. The elderly population and especially the oldest old were numerically irrelevant and their life expectation was short when they fell ill. Hence its inadequacy towards chronically ill, unstable, disabled and frail elderly individuals.

The general practitioner, who bears the greatest responsibility concerning healthcare. and responds to these patients’ needs both when they are "confined" to their homes and when they are admitted to nursing homes, lacks adequate preparation.

The hospital, which is in practice still the reference healthcare facility and which is not designed and created from an architectural, organisational and functional perspective to welcome this type of patients, is undergoing a gradual modification in its role, which increasingly focuses on treating severe cases (i.e. the DRG system). This trend is leading hospitals to avoid patients who need longterm care and whose problems have a "low" clinical complexity. They are inappropriately defined as such as they do not require expensive technologies. Though territorial services are the most appropriate proposal for healthcare issues related to chronic diseases, disablement and frailty, they have considerable deficiencies and are often not personalised. (Table 1)

|

Table 1 Background Features of Continuative Care (CC) Services |

There is plenty of evidence concerning the extent of this organization’s inadequacy: the fact that families carry about 80% of the healthcare load;

the so-called phenomenon of carers of the elderly, which by now counts an amazing number of elderly individuals who are not self-sufficient and are thus cared for at home by carers who lack all training. Besides the latter are generally from other countries, hence difficulties concerning mutual adjustment due to a different language and culture (Figure 7);

institutions and homes for the aged, which were initially designed to provide hospitality to the needy and poor elderly people who were alone in the world in their last moments, have become real "mini-hospitals", a concentrate of chronic diseases, disablement and psychophysical pain without adjusting structural, organisational and functional features to the different types of guests.

The so-called "difficult discharge" or the "blocked beds" phenomenon further stresses the current system’s total inadequacy. This problem, which is steadily and speedily growing, expresses hospitals’ impossibility to speedily discharge patients due to a lack of suitable territorial services.

Figura 7 - La crescita esponenziale del fenomeno delle badanti nel nostro paese (da “Repubblica”, 2005).

Figura 7 - La crescita esponenziale del fenomeno delle badanti nel nostro paese (da “Repubblica”, 2005).

GERIATRIC MEDICINE’S HEALTHCARE PROPOSAL

The healthcare method geriatric medicine proposes for such a complex patient as the frail elderly person is essentially based on three elements:

- comprehensive overall assessment;

- team work;

- continuative care.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)

This method’s validity and effectiveness have been proved by many controlled clinical studies on whose basis Guidelines have been drafted by a committee of dell’Asexperts as per the Ministry of Health’s proposal.

CGA or Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is an original method, which is considered as geriatric medicine’s technological tool "..., which enables to identify and explain the many problems of the elderly, assess their limitations and resources, define their need for care and process a programme for overall care and targeted interventions…".

It makes use of many tests and scales, which have been specially processed and validated for the elderly patient. When it is applied to the same patient at regular intervals and not only when a problem appears, CGA can:

identify elderly individuals who risk frailty or who are already frail; enable early detection of problems that are often misdiagnosed, thus enabling the implementation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic strategies;

assess the healthcare plan’s effectiveness. Many studies have been conducted in different healthcare settings – hospitals for serious cases, assisted long-term hospitalisation and homecare – which have proved the method’s effectiveness. Overall results, which have been assessed by meta-analysis, currently suggest that CGA applied to patient management leads to clear advantages both in terms of reduced mortality rates and especially of quality of life.

Team Work

This method is based on the fact that CGA cannot be conducted irrespective of collaboration between many professional figures.

Effective team work requires the following:

clear intervention goals that are common to all operators;

goals, which focus on the well-being of the elderly;

team members must have an equal degree of professional authoritativeness and they must be recognised specific competences;

all members must freely state their opinion with equal dignity;

team members must be satisfied, motivated and develop a strong sense of belonging and a constructive attitude;

an effective communication model between all team members. It must be ensured by using the appropriate tools (i.e. an interdisciplinary clinical report) and strategies for the management of contrasting opinions.

Continuative Care

The proposed model of care for the frail elderly is Continuative Care (CC), which is designed to provide answers that are constant, global and flexible in time. It is in fact the only model that can really take care of patients for whom sporadic and/or specialist interventions are entirely inadequate or rather pointless.

Besides responding in a qualitatively adequate manner to these patients’ requirements, this model has also proved to be economically advantageous as it reduces unnecessary hospitalisation, the so-called difficult hospital discharge phenomenon (or blocked beds) and, subsequently, the cost of hospital care, which influences health expenditure more than all other items.

The following points are essential for CC to reach its goals:

- all hospital and territorial services and facilities should adopt the same working method, which should be CGA;

- all services and facilities should be functionally linked also by an IT network;

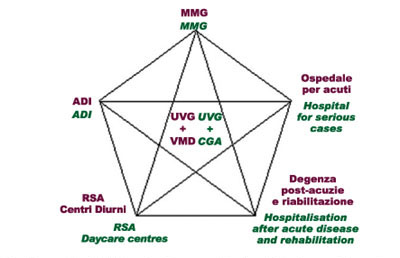

- there should be an operational team appointed to process plans for personalised care, to send patients to facilities and services envisaged by the network system and to check that the set goals are reached. This team, which is called Geriatric Assessment Unit (UVG), comprises a geriatrician, a social worker and a geriatric nurse who are assisted by a specialist in general medicine and other professional figures depending on the various problems and individual needs.

CONCLUSIONS

Population aging has involved a deep change in the need for care due to a considerable increase in chronically sick and disabled individuals and to a new emerging patient category, the so-called frail elderly who are characterised by extreme clinical instability and have a high risk of rapid decline in health and in the level of functional autonomy.

The current social and sanitary model cannot provide these individuals with an adequate response. Hence the need felt by all industrialised countries, which are experiencing the same demographical transition as Italy, for a new model designed to provide continuative longterm care by implementing a network of facilities and services that are functionally integrated among them.

The operational method required to ensure this network’s correct functioning is the so-called geriatric CGA, which has been validated by many studies.

Some of these studies have also been conducted in our country.

Unfortunately though this model of Continuative Care of the frail elderly is envisaged by the latest national health plans and by many regional health plans, to date it has been implemented only partly and in a limited manner due to budget limitations and especially due to a lack of "mentality-culture" concerning the population’s weaker category.

Umberto Senin

Director of the Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics - Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia.

Bibliografia

1. American Medical Association. White paper on elderly health. Arch Intern Med, 150: 2459-2472, 1990.

2. Brizioli E, Romano M, Senin U, Trabucchi M. La rete dei servizi per anziani. In: Trabucchi M, ed. Residenze sanitarie per anziani. Bologna: Fondazione Smith Kline, Il Mulino; 549-68; 2002.

3. Cester A. Il lavoro di equipe. In: Senin U, Cester A, Cencetti S. (Eds.) La valutazione multidimensionale geriatrica ed il lavoro di equipe. 157-161;1998.

4. Cherubini A, Dell’Aquila. La sarcopenia nell’anziano: definizione, significato clinico e trattamento. In http:/www.medsolve.it, 2004.

5. Cohen HJ, Harris T, Pieper CF. Coagulation and activation of inflammatory pathways in the development of functional decline and mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 114:180-7; 2003.

6. Corti MC, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, Sorkin JD. Serum albumin level and physical disability as predictors of mortality in older persons. JAMA. 272:1036-42; 1994.

7. Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, Sands LP, Yaffe K. The last 2 years of life: functional trajectories of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc.51:492-8; 2003.

8. Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM et al. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 47: 639-646; 1999.

9. Ferrucci L., Marchionni N., Abate G., Bandinelli S., Baroni A., Benvenuti E., Bernabei R., Brandi A., Cavazzini C., Carbonin P.U., Cesari M., Cherubini A., Corgatelli G., Cucinotta D., Di Iorio A., Frisoni G., Galluzzi S:, Giampaoli S., Landi F., Lauretani F:, Masotti G., Morosini P., Paolucci S., Rengo F., Salvioli G., Savorani G., Senin U., Taglietti P., Trabucchi M., Tratti Clementoni M. Linee Guida sull’utilizzazione della Valutazione multidimensionale per l’anziano fragile nella rete dei servizi. Giorn. Geront; 49:1-73; 2001.

10. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.56:146-56; 2001.

11. Fried LP, Darer J, Walston G. Frailty. In: Cassel CK, Leipzig RM, Cohen HJ, Larson EB, Meier DE (Eds.), Geriatric Medicine: An Evidence-based Approach, 4 ed.; Springer-Verlag, New York Inc., pp1067-1076; 2003.

12. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 59:255-63; 2004.

13. Hamerman D. Toward an understanding of frailty. Ann Intern Med. 130:945-50; 1999.

14. Hazzard WR. I’m a geriatrician. J Am Geriatr Soc. 52:161; 2004.

15. Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H; Steering Committee, Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging. Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res.15:1-29; 2003.

16. Hollander M., Pallan N. The British Columbia continuing care system: service delivery and resource planning. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 7: 94-109, 1995.

17. Masotti G., Senin. U., Marchionni N., Cherubini A., Ungar A., Fumagalli S. La valutazione multidimensionale geriatrica come strategia fondamentale in geriatria. In: Atti del 95° Congresso Nazionale della Società Italiana di Medicina Interna, 211-222, 1994.

18. Meschi T, Fiaccadori E, Cocconi S, Adorni G, Ridolo E, Stefani N, Schianchi T, Novarini A, Spagnoli G, Caminiti C, Pini M, Borghi L. Analisi del problema delle dimissioni difficili nell’azienda ospedaliera –universitaria di Parma. Ann Ital Med Int.19:109-117; 2004.

19. Morley JE, Perry MH, Miller DK. Something about frailty. Journal of Gerontology 57: 698-704; 2002.

20. Roubenoff R. Catabolism of aging: is it an inflammatory process? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 6:295-9; 2003.

21. Senin U. Paziente Anziano Paziente Geriatrico. Fondamenti di gerontologia e geriatria. Edises, Napoli, 1999. Ann Ital Med Int.18: 6-15; 2003.